Watchmen

𐑢𐑪𐑗𐑥𐑧𐑯

You find that, yes, superheroes in the real world are kind of funny. They're also kind of scary, because actually a person dressing in a mask and going around beating up criminials is a vigilante psychopath. That's what Batman is, in essence. We came up with the character of Rorschach as a way of exploring what that Batman type, driven, vengeance-fulled vigilante, would be like in the real world. And the short answer is: a nutcase.

— Alan Moore, 2007[1]

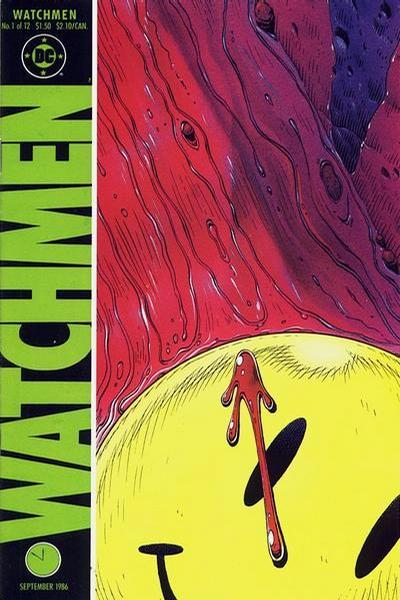

Watchmen #1

Watchmen was an influential comic released by DC from 1986 to 1987. It consists of a single limited series that was originally released as twelve comic book issues, then collected as a trade paperback. It was written by Alan Moore, illustrated by Dave Gibbons, and coloured by John Higgins.

Moore takes the ludicrous premise of superheroes and masked vigilantes existing, and treats it seriously enough to ask just what kind of people would dress up in strange costumes to fight criminals, and what would happen if someone with godlike powers tried to live in society. As a result, he inadvertently helped usher in the Modern Age of US comic books, with its darker tone and longer format.

It seems a fitting irony that Moore created Rorschach as an example of why a masked vigilante would be reprehensible, only for him to become a fan-favourite. It seems people saw in him what they wanted to, much like a Rorschach test.

Set in New York City in an alternate 1985, the Cold War ominously looms in the background, from fallout shelters to the Doomsday Clock, its minute hand echoed as spatter on the iconic 1960s smiley face that bookends the entire series.

Moore intended it to be read slowly, as it's densely packed with worldbuilding details. As one example, Jon Osterman accidentally attaining godlike powers makes Hollis Mason's vigilantism obsolete, even if he cites other reasons for retiring. He then becomes a mechanic, only for Osterman to synthesise enough lithium to make electric cars viable, making that job obsolete too.

The latter can only be inferred from the visible presence of electric cars that no-one mentions because they're taken for granted, and a sign in front of Mason's workshop declaring "Obsolete models a specialty." In a final indignity, Mason's subsequently murdered by a gang who mistake him for his vigilante successor, Daniel Dreiberg.

Deeper insight into the alternate world can be gleaned from visible headlines in newspapers, whether in stands, being read, or discarded, along with walls covered in both political posters and their opposing graffiti. Each issue's last few pages feature an extract from a fictional prose document, such as an office memo, psychiatric file, article, or biography.

Watchmen was released when just under half of the UK population had a low definition VCR.[2] At the time, the comic book was the only medium that was visual, detailed, affordable, and allowed you to easily flip back and forth to compare what was depicted on various pages. Moore, Gibbons, and Higgins embraced the comic book medium, playing up to its then-unique strengths. In turn, other writers and artists embraced some of their innovations within that medium, for both better and worse.

Quotes

We started out with all these innocent ideas, like making the smiley badge on the cover of the first one the first panel of the story, and then to be really clever we'll make it the last panel of the story as well, and have it on the last panel of the book. Then we did that with the statue in the second issue as well, and by that time it's a feature and you've got to do it every issue.

— Alan Moore, 1986[3]

Our intention was to show how superheroes could deform the world just by being there, not that they'd have to take it over, just their presence there would make the difference. It's what we try to show in Watchmen #4. From the point where Dr. Manhattan appears, it slowly starts to go downhill from there. Everything starts to change. He doesn't take over the country or make people subservient to him, but just his presence there makes everything begin to change. Yet on another level, if you equate Dr. Manhattan with the atom bomb, the atom bomb doesn't take over the world, but by being there it changes everything. That was more the idea that I was trying to explore.

— Alan Moore, 1986[3]

References

- "X-Rated: Anarchy in the UK" Comics Britannia, Sep 2007

- "Living in Britain" Olwen Rowlands, Nicola Singleton, Joanne Maher, Vanessa Higgins, Office for National Statistics, 1997

- "A Portal to Another Dimension: Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and Neil Gaiman" The Comics Journal, Jul 1987

Further reading

Interviews

- "A Portal to Another Dimension: Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and Neil Gaiman" The Comics Journal, Jul 1987

Comics: Comic book | DC Compact Comics | Graphic novel | Limited series | Masked vigilante | Modern Age | Superhero | Watchmen